As the Paris Peace Conference ground on through the early months of 1919, the situation in Germany was unsettled, chaotic, and dangerous, and not just in Germany but all over Europe, the Middle East, Asia, in short, all over the World. The issue was the role of government in controlling the lives of the citizens – the never ending clash between capitalism and socialism.

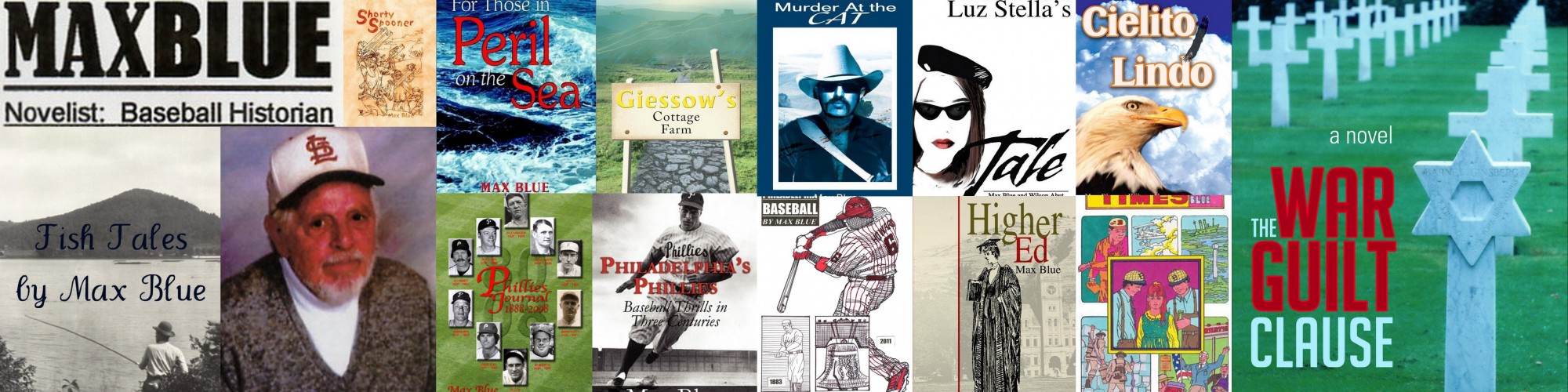

Below is yet another chapter that did not survive the cut in the original version of The War Guilt Clause

THE BAVARIAN SOVIET REPUBLIC

As the Supreme Council shuffled to gain its footing in Paris, the mood in Munich was somber, confused, and anxious about what the so-called peacemakers had in store for their defeated nation. The city was spared physical damage, to be sure, but, when 700 years of monarchial rule ended with the declaration of a free state of Bavaria on November 8, 1918, two days before Kaiser Wilhelm headed for exile in Holland, the citizens of Munich were faced with the new challenge of how to live in a system where the lines of authority were yet to be firmly established. It was rumored that they would be asked to vote.

“WAR IS PART OF GOD’S WORLD ORDER!”

The words thundered across the cobblestoned Munich square where a large crowd had gathered to listen to a man of all-too-obvious authority in the uniform of a German army officer, peaked cap firmly in place. Few knew he wore the tabs and markings of a general, and only a handful knew it was Erich Ludendorff, former commanding general of all German forces on the Western Front; he stood on a raised platform and used a megaphone to deliver his message. Ludendorff seethed with rage, an emotion that had consumed him from the moment on the fields of France when he realized that his armies had been defeated by the forces of international pacifism.

Hermann Grossman, the former Obergefreiter Grossman, of the third Royal Bavarian Division, had survived the war, and was beginning to wonder if he could survive the peace. Grossman stood near the center of the square, pressed on one side by a frenzied group straining to hear Ludendorff, and on the other by an equally agitated crowd trying to hear what Kurt Eisner, President and Prime Minister of the Free Republic of Bavaria, was saying. Eisner and Ludendorff on opposite sides of the square, and on opposite sides of the political spectrum, pounded their messages with the crusading zeal of one who believed that failure to follow their lead would result in death, destruction, and dishonor of the German Fatherland. Ludendorff and Eisner were miles apart on method, but in total agreement on outcome.

Grossman was in Munich to purchase a bundle of leather for his father’s shoemaker shop in Dachau, a medieval village some 20 miles north of Munich. The city and the land may have been in revolutionary uproar, but shoes were needed regardless of political preferences.

ZZZZZ

War, for the individual being, as well as the state, will remain a natural phenomenon, grounded in the divine order of the world.

The voice of General Ludendorff reached Grossman’s right ear.

ZZZZZ

We are not communists! We are the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany, and we believe in property rights for individuals.

And into his left ear, from the unruly hair-surrounded mouth of Kurt Eisner.

ZZZZZ

All very well, but in the overheated atmosphere of a staggering Germany, trying to pick itself up off the mat, Eisner had committed an unforgivable sin: he had admitted Germany’s responsibility for the Great War in a speech before the International Labor and Socialist Congress in Basle, Switzerland.

Less than an hour later, Eisner was assassinated by a descendant of the House of Hohenzollern – the royal family that had ruled Bavaria for more than 700 years; a right-wing radical named Count Anton Arco-Valley pulled the trigger.

ZZZZZ

Paris Le Temps

February 23, 1919

SOVIET REPUBLIC PROCLAIMED IN BAVARIAN OUTBREAK

State of Siege in Munich; Reds Seek to Avenge Eisner

ZZZZZ

Peggy Schooner read the headline in the Paris Times, shook her head in disgust, and handed the paper to Ed Frederick.

“I’m going to Munich,” she said.

“Why?” asked Ed. “Is it more important than what’s happening here in Paris?”

“What’s happening here will be determined by what happens there – don’t you see?” Peggy displayed a touch of impatience when Ed was slow to grasp a point.

Colonel House saw it very well and quickly dispatched two deputies, William Bullitt and Lincoln Steffens to Moscow (they had to travel through Sweden), their mission: meet with the Bolshevik leaders and determine what it would take for them to make peace with the allies. Bullitt and Steffens went with the erroneous impression that they had a mandate to negotiate conditions with the Bolsheviks. House was apparently under the erroneous impression that the left-wing uprisings in Germany, and more specifically in Bavaria, were controlled by the Bolsheviks.

Ed may have been slow to connect Munich with Paris in terms of the peace conference, but he was quick to see the opportunity to connect the two cities by means of the newly minted industry of civilian air travel.

“Ted will take us there,” he proclaimed.

Peggy speared him with a puzzled look; she had no idea who Ted was, and she was surprised when Ed used the word us.

“Who is Ted, and what do you mean, us?”

“My brother Ted is a pilot,” said Ed, “and he is in the business of transporting people by air; he works for a French company that has a regular schedule of flying people back and forth between London and Paris,” he paused, “Ted can fly us to Munich; I’m going with you,” he pronounced.

XXXXX

In Munich, chaos reigned; with the death of the moderate Eisner and some of his ministers, a power vacuum ensued. Johannes Hoffmann, Minister of Education under Eisner tried to carry on, but he was soon overwhelmed by a true communist movement headed by Eugen Levine.

XXXXX

Peggy Schooner and Ed Frederick, with his pigeon German, were there, and they were dodging bullets; if it wasn’t a civil war it was the next thing to it; it was the Reds against the Whites and it was ugly; people were getting killed, sometimes by execution.

ZZZZZ

APRIL IN MUNICH

Copyright 1919 by the New York Times Company

Special wireless and cable dispatches to the New York Times

by Edward Frederick

April in Munich

May 3, 1919

In the month of April, 1919, the independent state of Bavaria and its capital, Munich, were ruled by the Communist party, headed by a man named Eugen Levine. Backed by an army of 20,000 men, part of the more than three million nation-wide unemployed German workers, Levine wasted no time in implementing reforms reflecting hard-core communist philosophy: wealth must be shared. Luxurious apartments were expropriated and given to the homeless; factories were placed under the ownership and control of their workers.

Counter revolutionaries were arrested, suspected right-wing spies were executed including some princes, counts, and countesses.

It could not last, and Eugen Levine must have known it; when “the white guards of capitalism” came, 30,000 strong with their Freikorps, to confront him, he battled to the bitter end which for him was the hangman’s noose. The demise of German Communism, settled on the streets of Munich in the first week of May, 1919 must be seen as the triumph of Erich Ludendorff and all he stands for.

Attention Paris Peace Conference: Germany may be down, but she is snarling in her reduced circumstances, and far from out.

CITIZEN GROSSMAN SPEAKS

Special to the Chicago Herald-Examiner

by Peggy Schooner

in Dachau, Germany

May 3, 1919

Herr Grossman hammers the final nail into the sturdy leather shoe sole he is working on, and ponders an answer to the question I have posed: what is to become of post-war Germany?

He answers: “Much will be made of the verdict handed down by the Paris Peace Conference, but from my perspective it will not matter – no matter how harsh, no matter how lenient, the Germany of the conservative right is not defeated and when the next leader comes forth, men will follow him again into the jaws of war. Have you not heard General Ludendorff?”

Grossman has more to say about Ludendorff. He opens a drawer, takes out a newspaper and says, “Ludendorff may be that leader, listen to what he has written:

The renewal of the German Nation’s strength and spirit requires it to be unyielding and unified in deep Christian faith, glowing with love of the Fatherland and readiness to sacrifice for it. The un-German in and around us speaks lies; first and foremost in the lack of race feeling; in the elevation of intellectual training over manual skills; in internationalist, pacifist, and defeatist thinking; and finally in the strong intrusion of the Eastern European jewish people inside our borders.

Grossman now becomes animated as he thinks and speaks about Ludendorff. “What is this man thinking? He did not question my Jewishness when he sent me to attack Amiens. He calls me un-German? Preposterous.”

And so the shoemakers in Dachau, the farmers in their fields, the workers in the factories, the millions of unemployed men all over Germany, the hausfraus and their kinder, the students in their schools, the soldiers on their drill fields, hear the defiant words of the Generals in Munich and Berlin, and await their fate. The Peace Conference in Paris is convened; the German people wait

I’m glad you’re posting these deleted chapters. They’re interesting to read. However, I do have to say that I think the novel is stronger for omitting them. What you’ve posted so far has a tendency to fall more toward “tell” rather than “show.”

Pingback: Roger Mickelson’s History Today | Sandia Tea Party